Journey 023: Wanted: Husbands

The pilgrims ask for a night’s stay and get offered something much more.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Transcript

Welcome to the Chinese Lore Podcast, where I retell classic Chinese stories in English. This is episode 23 of Journey to the West.

Last time, the traveling party of scripture pilgrims was finally complete, adding Sha Zeng to their ranks at Drifting Sand River. Once they crossed over the river, master and disciples continued their trek to the West. As they traveled along the main road, they passed through countless green hills and blue waters and saw endless wild grass and flowers. Time flew by, and soon it was autumn again.

One day, dusk was approaching as they traveled, and San Zang asked his disciples, “It’s getting late again; where would we lodge tonight?”

“Master, you’re mistaken,” Wukong replied. “We traveling monks feast on the wind, stay by the water, rest under the moon, and sleep with the frost. Anywhere can be home, so why do you need to ask where we will lodge?”

But disciple No. 2, Zhu Bajie, piped up, “Brother, you just know that you’re traveling light and easy. You don’t care that others are tired. Ever since Drifting Sand River, we’ve been scaling mountains and ridges while carrying heavy loads. It’s hard! We need to find a household somewhere to get some food and to rest up a bit.”

“You dolt. You sound like you’re complaining. You think you’re still back at the Gao Family Village, living the lazy and easy life? That won’t do. In order to truly embrace Buddhism, you must endure suffering. Only then can you call yourself a true disciple.”

“But brother, look at how heavy this luggage is,” Bajie griped.

“Brother, every since we added you and Sha Zeng, I haven’t carried the luggage, so how would I know how heavy the luggage is,” Wukong retorted, which was kind of Zhu Bajie’s point. And Bajie did not hesitate to tell him in detail about the bulk of the luggage.

“Brother, count the stuff here:

Four golden rattan mats, eight cords of varying length.

To keep out wind and rain, they’re wrapped in several layers of felt.

To keep the yoke from slipping, it’s nailed fast at both ends.

An iron staff of nine rings, copper‑bound; rattan vines entwine the great cloak.”

“With so much stuff, you should pity me for walking all day while carrying this load. While you play disciple to our master, you’re just using me as a laborer.”

Wukong chuckled, “Dum-dum, who are you complaining to?”

“To you.”

“Well, you’re complaining to the wrong guy. I’m in charge of master’s safety, while you and Sha Zeng are in charge of the luggage and the horse. But if you slack off in the slightest, then I’m going to give you a beating with my rod!”

“Brother, don’t talk about beatings. That would be threatening someone by force. I know you’re too proud to carry the luggage. But look at how tall and strong master’s horse is. Yet it’s only carrying an old monk. Have the horse carry a few pieces of luggage, for your brother’s sake.”

“Horse?” Wukong scoffed. “That’s no ordinary horse. He’s the son of the Dragon King of the West Sea. Because he burned a sacred pearl, his father turned him in to the Jade Emperor. The Bodhisattva Guanyin saved his life. He waited at Eagle Grief Ravine for a long time for our master, and then the Bhodisattva showed up and made him turn into this horse to carry our master to the West. Each has his own duty and reward. Don’t butt in on his.”

Now, it seems rather odd that it’s taken this long for Sun Wukong to tell the newer members of the crew that hey, this horse is actually a sentient dragon, but apparently he hadn’t, because Sha Zeng now asked, “Brother, he’s really a dragon?”

“Of course!”

Bajie then piped in, “Brother, I heard the ancient say that dragons can breathe cloud and fog and stir up dirt and sand. That they can leap over mountains and peaks and churn rivers and oceans. So why is he walking so slowly?”

“You want him to go fast? I’ll show you fast,” Wukong said. He then pulled out his golden rod and acted like he was about to take a swing at the horse. Now, c’mon man, that ain’t cool. You were just telling everyone else that he’s a sentient dragon. In any case, the horse saw the rod come out and immediately panicked and took off like lightning. San Zang couldn’t rein it in and could only hang on for dear life while the horse sprinted up the mountainside before slowing down.

Catching his breath, San Zang looked up and saw a stretch of shady woods, within which stood several houses. Beneath the pine trees, he saw:

Doors draped in emerald cypress, houses beside jade‑tinted hills.

A handful of pines standing tall and slow, and spotted bamboo stalks below.

Wild chrysanthemums by the fence bloom bright with frost,

while orchids by the bridge cast ruby in the pool.

Soft‑white plaster walls and circular bricks enclose the scene;

A lofty hall standing majestically, the mansion calm and serene.

No sign of oxen, sheep, chickens, or dogs —

It seems the autumn harvest is done and the farm is at ease.

While San Zang looked on, his disciples caught up.

“Master, you didn’t fall off the horse, did you?” a concerned Sha Zeng asked.

San Zang said angrily, “That brazen ape scared the horse. Good thing I was able to hang on!”

Wukong put on a big smile and said, “Master, don’t scold me. It was Zhu Bajie who complained that the horse was going too slow, so I made it go faster.”

Bajie, meanwhile, was still trying to catch his breath from trying to catch up to the horse. As he huffed and puffed, he grumbled, “That’s it; I’m done! Look at how slack my belly is. The luggage is so heavy that I can barely carry it, and now I have to run after the horse!”

San Zang now suggested they go seek lodging for the night at the manor up ahead. Wukong took a quick look and noticed that auspicious clouds had gathered high up in the sky above the houses. He knew something was happening here, but he also didn’t want to drop any spoilers. So he just said sure, let’s go.

San Zang dismounted as they approached an ornately decorated entryway. While Sha Zeng put down the luggage, Bajie took hold of the horse’s reins and said, “This must be a wealthy family.”

Wukong was just about to enter, but San Zang said, “Hold on. We’re monks. We must avoid suspicious behavior and not just barge in. Let’s wait till someone comes out, and then we can ask for lodging.”

So Bajie hitched the horse and slumped against the foot of a wall. San Zang sat down on a stone drum, while Wukong and Sha Zeng sat down by the gate. And so they waited, and waited, and waited. A long time passed, and still no one came out.

By now, Wukong was getting impatient, so he hopped up and skipped through the gate to have a look inside. He saw three large parlors, all facing south and all with their door curtains pulled up. Above the door stretched a horizontal scroll painting depicting motifs of long life and rich blessings.

On both sides of the door stood pillars painted in gleaming gold lacquer, on which were pasted a couplet, which said, “Frail willows float like gossamer, the low bridge at dusk; snow dots the fragrant plums, a small yard in the spring.” In the center of the hall, there was a small black lacquer incense table, its luster faded. On the table stood a bronze incense pot. There were also six chairs and screens hanging on the east and west walls.

While Wukong was stealing a peek, he suddenly heard footsteps from beyond one of the doors. Out came a middle-aged woman who said, “Who is barging into the home of a widow?”

That put Wukong on notice, and he said respectfully, “I am from the Great Tang Kingdom in the East. We’re on our way to the West to see the Buddha and request scripture. There are four of us. We were passing by your honorable estate when it got late, so we came here to ask for lodging for tonight.”

The woman immediately smiled and welcomed Wukong and asked where his three companions were. Wukong now called out, “Master, please come in.”

Only then did San Zang enter, followed by Bajie and Sha Zeng with the luggage and horse. The woman went out to welcome them, and Bajie stole a glance at her. She was clad in a gown of mandarin green and silk brocade, a pink vest, and a light yellow embroidered skirt. Beneath her skirt, you could see high-heeled, floral shoes. Her bun was stylishly covered with loose black gauze, set off by two-toned braids. In her hair there was an ivory comb that gleamed in red and emerald, askew with two red-gold pins. Her sideburns looked like drifting clouds, half turned silver and spread like phoenix wings. A pair of pearl earrings dangled from her lobes. She wore no powder or rouge, but she also didn’t need it, as h er elegance still shined with the charm and beauty of a fair youth.

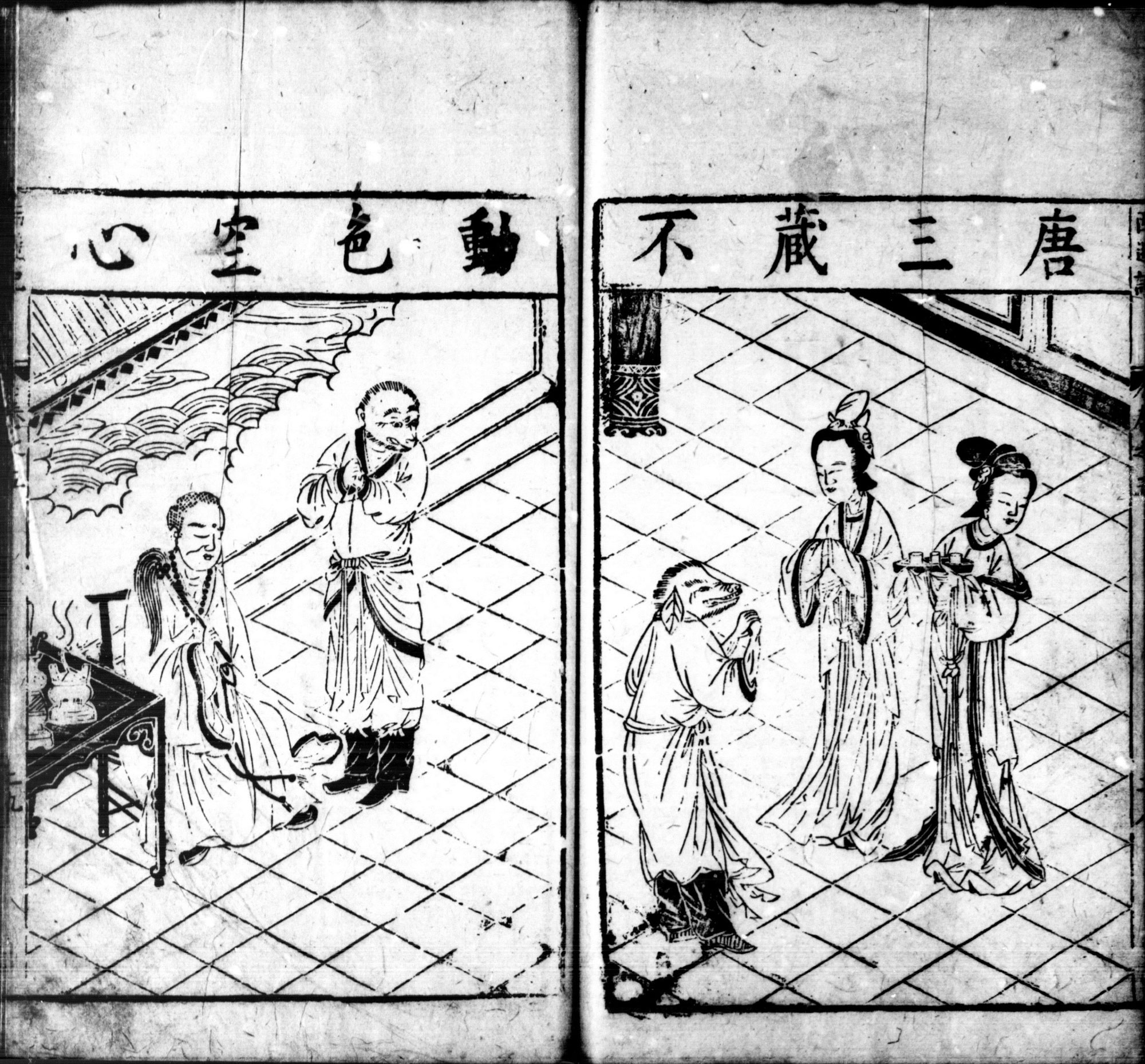

The woman was delighted to see the other three members of the party, and she warmly welcomed them into the parlor and greeted them each, then asked them to sit and receive tea. From behind the screen emerged a young girl, whose twin hair buns were draped with flowing silk ribbons. She held a golden tray, on which sat white jade cups that held fragrant tea and exotic fruits. The woman rolled up her colorful sleeves, revealing long, delicate fingers like stalks of spring onions, and held up the jade cups, passing tea to each of her guests, bowing as she did so.

After tea, the woman told the girl to go prepare dinner. San Zang then asked, “Old Bodhisattva, what is your honorable last name? And what is the name of this esteemed place?”

And by the way, the moniker Old Bodhisattva was a figure of speech referring to women acting with compassion. The woman answered San Zang, “This is the Western Continent. My last name is Jia (3), and my husband’s last name is Mo (4). Unfortunately, my in-laws died early, so my husband and I inherited their property. We have tens of thousands of strings of coins and vast fertile farmland. But we had no sons, just three daughters. Last year, bad luck struck again and my husband died. I have recently completed my period of mourning. Now I’m left with all this farmland and property, but no relatives. It’s just me and my daughters. I thought about remarrying, but didn’t want to give up my property. So I’m delighted that the four of you showed up. My daughters and I are willing to take you as husbands. What do you think?”

When he heard this, San Zang just acted like he was deaf and mute, as he sat there with eyes closed and made no reply. The woman now continued, “We have 300 acres of wet farmland, 300 acres of dry farmland, and 300 acres of orchards. We also have more than 1,000 water buffalo, herds of horses, and countless pigs and sheep. We have about 70 pastures around our manor, enough grain to last a decade, enough fabric for dozens of years, and more gold and silver than you can spend in a lifetime. What can be better? If you four are willing to stay here and be our husbands, you will live carefree and enjoy all the luxuries of life. Isn’t that better than wearing yourselves out trying to reach the West?”

To all this, San Zang just sat completely silent. The woman again continued, “I was born in the hour of the rooster, on the third day of the third month. My deceased husband was 3 years older than me. I’m 45 this year. My eldest daughter, named Zhen zhen (1,1), is 20. My second daughter, named Ai Ai (4,4), is 18. My youngest daughter, named Lian Lian (2, 2), is 16. None of them have been promised to anyone yet. Even though I am ugly, fortunately my daughters are all pretty, and they are skilled in all the womanly crafts. And because my dead husband didn’t have any sons, he raised them like sons. So he taught them some classics when they were young, and they know how to compose a bit of poetry. Even though we live in the mountains, they are not rubes. I think they would be good matches for you all. If you are willing to let go of your religion, regrow your hair, and stay here to be our husbands, you will wear fancy clothes. That would beat the attire of a monk.”

By now, San Zang looked like a child frightened by thunder, a toad drenched by rain. His eyes bulged and rolled, and he could barely keep himself upright in his chair. Zhu Bajie, meanwhile, was having different feelings. When he heard the woman describe her wealth and her daughters, his heart started to itch, and he could barely sit still. He twitched in his seat as if a needle was pricking him in the rear. Finally, he couldn’t take it anymore. He popped up, walked over to San Zang, pulled on his sleeve, and said, “Master, our hostess is talking to you. Why are you ignoring her? You should at least acknowledge what she’s saying.”

San Zang’s gaze shot up, and he scoffed and scolded Bajie, “You beast! We’re monks. How can we allow ourselves to be moved by wealth and beauty?!”

The woman chuckled, “Oh dear. What’s so great about renouncing the world?”

“Lady bodhisattva, what’s so great about living in the world?’ San Zang retorted.

“Elder, please sit and let me tell you all about it. Listen to this poem:

Spring’s tailor‑made robes outshine the finest silk;

Summer brings gauzy veils to admire the jade‑green lotus.

In autumn we sip fresh, fragrant glutinous‑rice wine;

Come winter, warmed by pavilions, our cheeks glow with delight.

Each of the four seasons offers its own pleasures,

And the eight holidays bring sumptuous delicacies in abundance.

Beneath brocade and spread on satin, candles flower through the night,

It’s better than a pilgrim’s solemn homage to Amitābha.”

But San Zang said, “You get to enjoy luxuries and wealth. You dress well and eat well, and you get to be with your children. That’s all great. But the lifestyle of monks also has its benefits. Listen to this poem:

To take the vow and leave the world is truly an act supreme,

Tearing down the halls of past desires.

No worldly trifles stir the tongue—within, perfect balance reigns.

When we have made our merit, we stand before the Golden Arch.

Knowing our nature, heart made clear, we return to our true home.

It’s far better than craving flesh at the hearth,

lest in our old age we fall back into this rotting fleshly frame.

The woman became irate when she heard that poem. “You rude monk! If not on account of you being from the East, I would kick you out. I sincerely offered you our property and ourselves, and yet you insult me. Maybe you’ve received the precepts and have taken the vow to never return to the world. But I could at least get one of your disciples. Why are you so obstinate?”

Her rage intimidated San Zang, so he said, “Wukong, why don’t you stay here?”

But Wukong replied, “I have never known how to handle that sort of thing; just have Bajie stay instead.”

Zhu Bajie harumphed, “Brother, don’t put words in my mouth. Let’s talk it over carefully.”

“Well, if you two won’t stay, maybe Sha Zeng will,” San Zang said.

But Sha Zeng said sternly, “Master, what kind of idea is that? Thanks to the Bodhisattva’s guidance, I received the precepts and waited for you. And I have received your instructions ever since you took me in. I’ve followed you for two months and haven’t achieved any merit yet. How would I dare to chase after this wealth? I would risk my life to go to the West, and I will never do such a dishonorable thing.”

Seeing all four of them refusing her offer, the woman stormed off, going behind the screen and slamming the door behind her. Master and disciples found themselves alone, with no tea or food, and no one else in sight.

Now left by themselves, Zhu Bajie grumbled to San Zang, “Master, you just don’t know how to handle things. Your reply shut the door. You could’ve just muttered something noncommittal to string her along so we can get some food and get pampered tonight. Then tomorrow, whether we say yes or not, that’s totally up to us. But now, she’s shut the door on us and won’t come out. We have nothing but ashes and a cold stove. How can we make it through this night?”

Sha Zeng got annoyed when he heard that. “Brother, then you can stay and be their son-in-law,” he scoffed at Bajie.

“Brother, don’t put words in my mouth,” Bajie protested half-heartedly. “Let’s just think about the big picture.”

“What big picture?” Wukong cut in. “If you’re willing to stay, then you can be their son-in-law. They have plenty of money, so they’ll no doubt give us a big dowry and prepare a big feast for us in-laws. Then we get a little benefit, and you get to stay here and return to a secular life. It’s win-win.”

“You can say all that, but then I would have left the secular life behind only to return to it, and I would have left a wife only to take another,” Bajie protested, quarter-heartedly.

“Brother, you were married?” Sha Zeng asked in surprise.

“Oh yeah!” Wukong said. “He was the son-in-law for an Old Mr. Gao back in the Wu (1) Si (1) Cang (2) Kingdom. But then I brought him to heel, and he had also received the precepts from Guanyin, so he had no choice. I captured him and forced him to be a monk, so he gave up his wife to follow master to the West to see the Buddha. He must be missing that life and is thinking about it again. So when he heard the offer just now, he felt the urge. Hey dum-dum, just stay here and be their son-in-law. Just make sure to bow to me a few times, and I won’t report you.”

Bajie cried out, “Bullcrap! Bullcrap! Everyone here was tempted, but you are just picking on me. As the saying goes, ‘Monks are lust-hungry ghosts.’ Which one of us can truly say that he doesn’t want this? But you all have to put on a show, and now your historionics have ruined a good thing. Now we can’t even get a drop of tea or water, and no one will even give us a light. We may be able to make it through tonight, but that horse has to carry master tomorrow and travel. If it goes hungry tonight, we might as well skin it. Uh … why don’t you all sit while I go take the horse out to graze.”

As he said that, Bajie hurried outside, unhitched the horse, and led it out to graze. Once he was gone, Wukong said, “Sha Zeng, you stay here and keep master company. I’m going to follow him and see where he’s going to graze.”

“Wukong, you may go look in on him, but don’t ridicule him,” San Zang said.

Wukong nodded, and then he walked outside, turned into a red dragonfly, and flew out of the front door. When he caught up to Bajie, he saw that the latter was leading the horse but walking right past places where there was grass. Instead, he hurriedly went around to the back of the manor, where he came upon the woman and her three daughters standing around, looking at chrysanthemums, and having fun.

As soon as they saw Bajie, however, the three daughters ducked inside the house. The woman stood in front of the door and asked Bajie what he was doing there. Bajie dropped the reins, bowed, and said, “Mom, I’m leading the horse out to graze.”

“Your master is too squeamish,” the woman said. “Won’t marrying into our house be much better than being a monk trudging West?”

“Well they’re traveling West on the command of the Tang emperor, so they don’t dare to disobey their orders. That’s why they’re refusing your offer. Just now in the front parlor, they were all making fun of me. And I was a bit embarrassed because I was afraid you would think me ugly because of my long snout and big ears.”

“Well, I don’t mind. We have no man at home, so I want to get one. But my daughters might mind a bit.”

“Mom, please tell your lovely daughters to not pick men in that way. That Tang monk, for instance, may be handsome, but he’s useless. I may be ugly, but there are a few principles that I live by.”

“Like what?”

“Well, even though I’m ugly, I am diligent. I don’t need oxen or plow to till a thousand acres. One round with my rake, and seeds will grow. If you lack rain, I can summon rain. If you need wind, I can call the wind. If you think your house is too low, I can add two or three stories. If your ground is dusty, I will sweep it. If your ditches are clogged, I will clear them. All the affairs of the house I can take care of.”

Upon hearing that boast, the woman said, “Since you can manage a home, then go talk to your master again. If he’s ok with it, then I’ll take you as a son-in-law.”

“No need to discuss with him,” an eager Bajie said. “He’s not my birth parent, so it’s all up to me.”

“Fine, fine, fine,” the woman said. “Let me go talk to my daughter.”

And with that, she disappeared inside the house, closing the door behind her. Bajie, meanwhile, just led the horse right back to the front, without ever stopping to graze.

Unbeknownst to him, however, Sun Wukong was hovering in the vicinity the whole time and saw everything that went down. He now flew back on ahead. When he saw San Zang, he told him, “Bajie went to lead the horse.”

Now, Wukong was imbuing the phrase “lead the horse” with a double meaning, but that just completely went over his master’s head.

“Well if Bajie doesn’t lead the horse, it might run away,” said San Zang, not getting the joke and also once again forgetting that, hey your horse is a sentient dragon who has pledged himself to escort you to the West just like everyone else in your party.

Wukong started laughing and recounted everything that went down between Bajie and their hostess. San Zang didn’t know whether to believe him or not. But before long, Bajie came back.

“Did you lead the horse out to graze?” San Zang asked him.

“Uh, there’s no good grass, nowhere to graze,” Bajie replied.

“There’s no place to let the horse graze, but was there a place to ‘lead the horse’?” Wukong asked.

Now, Bajie DID understand the double meaning, so he knew that his secret was out. He could only lower his head, pucker his snout, and furrow his brow in silence.

Just then, the door to the room opened. Their hostess and her three daughters entered, preceded by a pair of red lanterns and an incense pot. The woman introduced her daughters, all of whom looked irresistibly gorgeous. San Zang just clasped his palms together in prayer and lowered his head. Wukong ignored the women, while Sha Zeng turned his back to them.

Zhu Bajie, on the other hand, just stared at them without blinking while his mind raced with impure thoughts. After a few moments, he said quietly to his hostess, “Mom, please ask your daughters to give us the room.”

The three daughters promptly went behind the screen, leaving behind the pair of red gauze lanterns. The woman now asked the pilgrims, “Elders, did you all pay attention? Who among you will marry my daughters?”

Sha Zeng replied, “We’ve talked it over. That Zhu Bajie is going to stay and marry into your house.”

“Brother, don’t frame me! Let’s … discuss the big picture,” Bajie protested, still maintaining the thinnest sliver of pretense.

“Discuss what? You had already come to an agreement by the backdoor,” Wukong said. “You even called her Mom, so what is there to discuss? Our master and this lady can serve as the parents. I’ll be the guarantor, and Sha Zeng can be the matchmaker. And no need to consult a calendar. Today is an auspicious date. Come bow to master, and then go be a son-in-law.”

“That won’t, that won’t do,” Bajie continued to fake-protest. “I can’t do that!”

“Dum dum, stop pretending!” Wukong said. “How many times have you called her Mom already? So what’s with the ‘I can’t do that’? Hurry up and close the deal, so that we get to drink a celebratory cup of wine.”

So he now grabbed Bajie in one hand and gestured toward the woman with the other, saying, “In-law, come take your son-in-law inside.”

While Bajie started to walk toward the private quarters, the woman summoned her maid and instructed her, “Wipe down the table and chairs and prepare a dinner for my three relatives here. I will take the groom inside.”

She then gave instructions to prepare a wedding banquet and ceremony for the next morning. Several maids snapped to and prepared a dinner for the remaining pilgrims, who ate and then set up their beds.

Meanwhile, Zhu Bajie followed his soon-to-be mother-in-law into the back of the manor, ready to embrace his new life as the man of the house. To see what the house had in store for him, tune in to the next episode of the Chinese Lore Podcast. Thanks for listening!

Music in This Episode

- “Luỹ Tre Xanh Ngát Đầu Làng (Guzheng) – Vietnam BGM” by VPRODMUSIC_Asia_BGM

- “Slow Times Over Here” by Midnight North (from YouTube audio library)